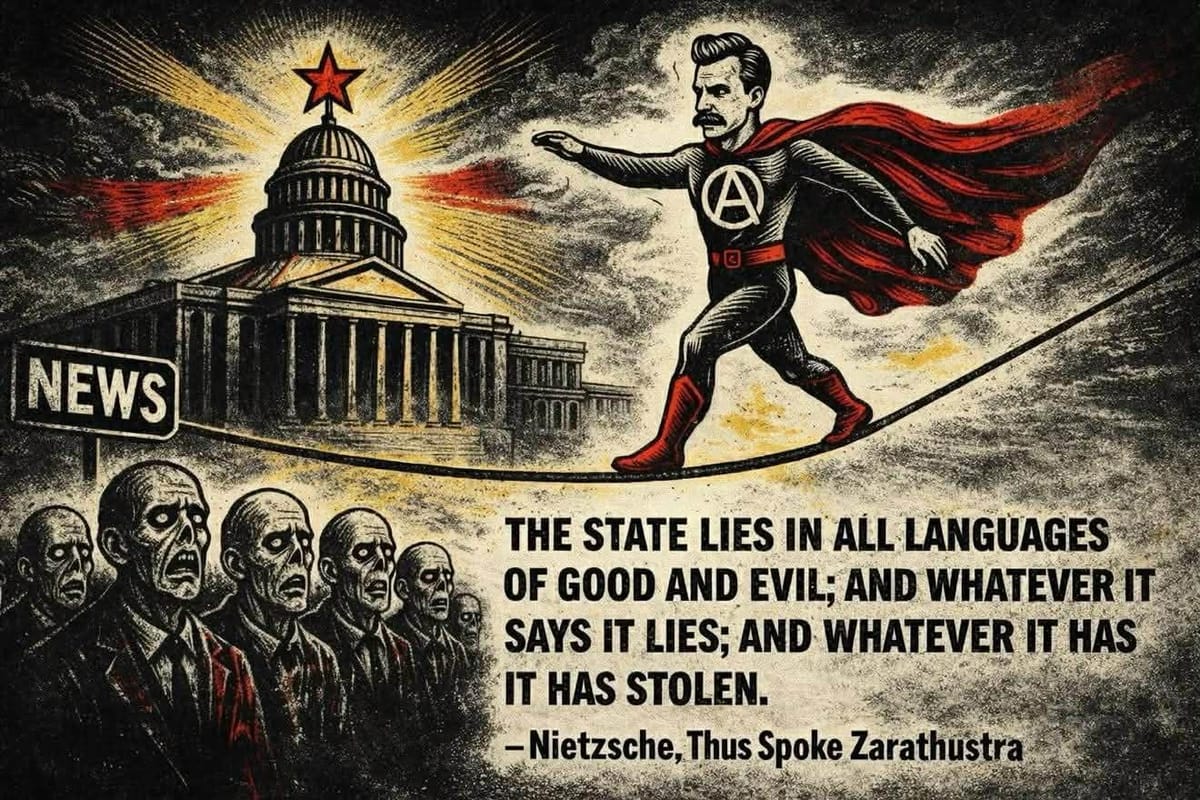

Anarchism and the Rights

Rights Beyond the State: An Anarchist Inquiry into the Source of Rights

The concept of rights is currently a prominent subject in political discussions. While some people view rights as bestowed by a divine power (God-given), others believe they are inherent (natural or unalienable), and still others argue that rights are merely social constructs. Generally, the right-wing political stance emphasizes the protection of rights based on religious or faith-based principles. In contrast, the left-wing approach with the exception of anarchism typically seeks to protect the rights of marginalized or oppressed groups by utilizing the power of the state to counter the influence or resistance of conservative forces.

Do the rights come from God?

For many religious conservatives and nationalists, rights are not a human creation but a divine endowment, flowing directly from either God or deities. An example of such a view could be the inherent dignity granted to every person—a concept seen in Christianity's Imago Dei (Image of God). This theological basis is also shared, with differing details, across faiths like Judaism and Islam. Historically, the religious notion that rights are divinely bestowed rather than state-granted has ironically resulted in situations where religious authority itself limited individual freedoms. For example, the Catholic Church condemned Galileo Galilei's heliocentric views as blasphemy, threatening his life and freedom of critique because his scientific position challenged their theological doctrine.

Similarly, in historic Islamic societies, non-Muslims were required to pay the Jizya tax to secure protection of their rights, effectively relegating them to second-class citizen status according to religious teachings. The supposed rights granted by religious teachings are actually oppressive constraints on individuals, dictated by the religions' own false or contradictory moral principles. These examples demonstrate that while religious doctrine establishes the inherent worth of individuals, the practical standard of rights often yields to the moral and ethical dictates of religious authority, especially when that authority is institutionally challenged.

In Hinduism, a system of caste-based discrimination has historically existed. This social structure, sanctioned by certain Hindu scriptures, established the Brahman class as superior while simultaneously declaring the Dalits (formerly "Untouchables") as "filthy" and effectively dehumanizing them. This created a rigid class structure within society where rights and dignity were severely unequal.

Liberalism and its view on Rights

John Locke, the father of Liberalism, argued in his Two Treatises of Government that individuals possess inherent rights to life, liberty, and property. For John Locke, the government consequently the state is created to protect the rights of the individual. Despite its internal contradiction—the irony of early liberalism simultaneously upholding individual liberty while also securing the property right to own other human beings (slavery)—the tradition must still be acknowledged and appreciated for its success in securing the rights of millions of individuals against tyranny.

F. A. Hayek, a prominent classical liberal, rejected the idea that rights are either divinely bestowed or rationally planned, arguing instead that they emerge from the spontaneous evolution of tradition and law. He viewed these rights as both the necessary result and precondition of an impersonal Rule of Law that developed to safeguard individual liberty. Hayek underscored this view by distinguishing between negative rights (like free speech and religion), which restrain the state and protect individual freedom from government interference, and positive rights (like the right to vote), which are merely privileges granted by the state. This distinction highlights a crucial point: contrary to the common assumption that the state bestows rights, they fundamentally also serve as a restraint on the state's power over individuals.

Post-Liberal views on Rights

The Marxist-Leninist/Stalinist view fundamentally dismissed liberal democratic rights (such as free speech and due process) as merely "bourgeois rights," arguing they were historically created by the capitalist class solely to protect its economic interests, especially private property. Under the Soviet system led by Stalin, individual rights were effectively nullified and redefined as collective rights, where their value derived from the good of the proletariat. Since the "vanguard party" claimed to possess the only correct view of history, it insisted that all its actions were in the people's best interest. In the Soviet system, rights were conditional and collective, granted only to serve the interests of the proletariat and the socialist revolution, thereby erasing individuality in favour of the class. Similarly, in fascism, rights were subordinate and conditional, existing only to the extent that they served the State and the Nation, demanding that the individual exist for the collective. Fascists shared the Marxist-Leninist view that the state and the nation are the source of collective rights, effectively erasing individuality as bourgeois.

Ultimately, both were systems where the individual's liberty was entirely dependent on their utility and conformity to the supreme, all-encompassing demands of the ruling power (the Vanguard Party or the Totalitarian State). For both fascism and Marxism-Leninism (actually existed socialisms), the rights are privileged for an individual to earn by showing their loyalty to the respective causes, let it be the red socialism of Stalinism or let it be the yellow socialism of classical Fascism. Both ideologies dismissed the liberal concept of individual rights and individualism as "bourgeois" fantasies that weakened the collective.

Lenin, equated individualism as bourgeois custom in his article “Party Organisation and Party Literature”:

● In contradistinction to bourgeois customs, to the profit-making, commercialised bourgeois press, to bourgeois literary careerism and individualism, “aristocratic anarchism” and drive for profit, the socialist proletariat must put forward the principle of party literature, must develop this principle and put it into practice as fully and completely as possible.

Edouard Berth, a key figure who transitioned from revolutionary syndicalism to proto-fascist national syndicalism, echoed this similar narrative in his article "Anarchism and Syndicalism":

● The bourgeois does not know what a national or a working-class collectivity is, nor can he, without any doubt, understand that the honour of this collectivity is something that is superior to a calculus of profit and loss. The bourgeois is a true individualist anarchist; for him nothing exists except his ego; he is rootless, a cosmopolitan, for whom there are no countries or classes: do not ask him to sacrifice his precious person for anything; he has no social idea, and the words self-abnegation and sacrifice have lost all meaning for him.

Both Marxist-Leninists and fascists reject individualism in favour of a collective identity or cause, often falsely condemning it (and egoism) as a bourgeois custom, a mistake famously made also by Karl Marx and Engels in their critique of Max Stirner. According to Daniel Guérin, Marx and Engels mistakenly believed Stirner's criticisms of communism were reactionary, failing to recognize that Stirner was actually targeting the "crude" State communism of his contemporary Utopians like Weitling and Cabet, which Stirner correctly saw as a threat to individual liberty.

Libertarianism and its view on Rights

A key figure of libertarianism, the mutualist anarchist Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, explicitly grounded rights in individual autonomy and social interaction. For him, rights are the product of individuals "agreeing with each other" out of an instinctive need for solidarity and a rational commitment to liberty and equality, as demonstrated by his core principle:

● “No one is obliged to do more than comply with this injunction: In the exercise of your own rights do not encroach upon the rights of another; an injunction which is the exact definition of liberty.”

Despite proposing this radical shift in how rights are sourced, Proudhon rejected the creation of a rigid blueprint, stating,

● “Nevertheless, I built no system. I ask for an end to privilege, the abolition of slavery, equality of rights, and the reign of law. Justice, nothing else; that is the alpha and omega of my argument: to others I leave the business of governing the world.”

Murray Rothbard, a pivotal figure who transitioned from early left-libertarianism to become the founder of paleo-libertarian movement, posited that rights are universal, absolute, and objective, stemming from the rational nature of humanity and the logical structure of reality, existing independently of any government, divine decree, or custom. He viewed the State as the single greatest violator of these natural rights, which he ultimately defined entirely as property rights. For Rothbard, rights originate from voluntary interaction between self-interested individuals who understand these rights, especially property rights, are essential for their protection. He clarified this absolute focus by reducing even common human rights to property rights:

● “In short, a person does not have a 'right to freedom of speech'; what he does have is the right to hire a hall and address the people who enter the premises. He does not have a 'right to freedom of the press'; what he does have is the right to write or publish a pamphlet, and to sell that pamphlet to those who are willing to buy it (or to give it away to those who are willing to accept it). Thus, what he has in each of these cases is property rights, including the right of free contract and transfer which form a part of such rights of ownership. There is no extra 'right of free speech' or free press beyond the property rights that a person may have in any given case.”

It’s important to note that the central contrast in political philosophy lies in the source of rights: while systems ranging from Religious Conservatism to Marxism-Leninism and Fascism share the fundamental premise that "The rights come from above, not from below"—they are granted, not inherent—the libertarian tradition, encompassing both left and right wings, breaks this consensus.

Where do the Rights come from: the Individual or the Collective

However, this whole left and right libertarian tradition still forget the obvious part which The German philosopher Max Stirner explained:

● “I do not step shyly back from your property, but look upon it always as my property, in which I respect nothing. Pray do the like with what you call my property!”

Through his declaration of radical self-interest (egoism), which utterly rejected all external moral, legal, and authoritative claims on the individual, including the traditional concepts of rights and property, he reminds the world of the idea that rights are granted by or protected by the state is a delusion; instead, he reminded the world that rights are always subject to challenge by authorities and the state, as well as by any individual strong enough to assert their will. His philosophy ultimately rests on the individual's absolute sovereignty and power. He famously said:

● “The state calls its own violence law, but that of the individual, crime.”

He reminds of how absurd the liberal claims of the state being an entity protecting the rights by asking that

● “The workers who ask for higher pay are treated as criminals as soon as they want to compel it. What are they to do?”

That indeed raised an important question. Were the workers given a safe and sound working environment from the beginning?

The slavery was ended by the abolitionist movement. Modern day working conditions of 8-hour day and five-day work weeks were linked to the Haymarket massacre where anarchists adopted syndicalism to fight back. The state was forced to compromise.

As Stirner said in the Unique and Its Own:

● The labourers have the most enormous power in their hands, and, if they once became thoroughly conscious of it and used it, nothing would withstand them;

● The State rests on the — slavery of labour. If labour becomes free. the State is lost.

Thus, for anarchists, the rights neither come from the state nor the gods but earned by the individuals and their collective power without sacrificing their individuality.

The Conflict of Rights

What is currently referred to in political discourse as the "culture war" can be paraphrased as a series of conflicts initiated by various interest groups that have ultimately consolidated into a struggle between two dominant pressure groups of elites, one representing Keynesian left and the other representing the right-wing conservatives.

When health freedoms are rights granted by the state, the power to decide what is legal for healthcare, such as abortion, becomes a conflict between competing political pressure groups. For instance, conservative groups will lobby against abortion rights and the bodily autonomy of people capable of pregnancy, arguing that the state should recognize a fetus as a human being. Ignoring moral or religious arguments, the ultimate outcome of this conflict can be predicted by material power: the collective bargaining strength of the people capable of pregnancy, whose labour can threaten the state, is far superior to that of the foetus, which possesses no corresponding labour power. Their real rival is the conservatives who will also pressure the state with the opposite political agenda. While it may sound uncommon, the reality of rights in relation to states is that legality, not morality, dictates individual freedoms. This explains why practices like slave ownership and identity-based discrimination were legal in the past but are prohibited today. The legal status of a right is entirely contingent upon the reigning political and legal system, which was shaped by the collective bargaining power of the oppressed individuals (let it be slaves or any other oppressed group). When the state establishes education as a granted right, the content of the curriculum inevitably becomes a battleground for pressure groups, reviving the historic philosophical conflict over who holds the ultimate authority to educate children: the parents or the state. Anarchists must closely scrutinize any political group that advocates for increased state power, as this directly contradicts their anti-authoritarian principles. The expansion of the state through left-wing policies like Keynesianism and the welfare state is considered just as concerning as the outbreak of right-wing populism.

The State has historically functioned as a tool of the elites, and it's crucial to understand that rights are not freely granted by the State out of goodwill. Instead, these rights are victories won through collective power and intense struggle. Therefore, the immediate goal must be to reclaim the State from the elites and return it to the masses, even if the ultimate objective remains moving beyond the State entirely.

Conclusion

Anarchism fundamentally envisions a society built upon free individual choices, which naturally develop into diverse communities—such as mutualist or communist systems—depending on the preferences of their inhabitants. In this framework, fundamental liberties are protected: individuals retain the right to hold their own political beliefs and the freedom to migrate to the specific anarchist community (e.g., a communist collective or a mutualist zone) whose economic and social model aligns with their personal values. In that way, for a society, freedom is upheld and protected by the individuals themselves, not by a state. This is because a violation of one person's rights is seen as a violation against all. Once mutual human respect and voluntary association break down, the door is opened to tyranny, fundamentally compromising the essence of a non-hierarchical society.

Even within non-anarchist societies, the genuine source of rights is not the state or society, but rather the individual and their collective bargaining power. These organized individuals assert their rights by strategically sabotaging the state through collective power. This power eventually forces the state to acknowledge and respect their demands, making the collective bargaining strength of the united individuals too potent to resist.