Instrument for Curating Ethnocracy

The recent killing of Renee Good by ICE has catalyzed renewed protest activity and intensified public debate over the use of extreme force in the policing and deportation of immigrant communities. ICE interventions increasingly arrive as fully militarized incursions, prepared to transform the city blocks in which they operate into temporarily saturated political spaces—zones of heightened coercion and symbolic domination in which right-populist power is enacted. Each episode of ICE violence, when displayed before surrounding communities, functions as a temporal epiphany of polarization and politicization: a brief but potent window into the trajectory of worsening social tensions.

These operations unfold before publics that are simultaneously subjects of and witnesses to violence. Residents often record events as they occur, thereby becoming unwilling archivists of state-produced trauma. This footage is then replayed thousands or millions of times across social media platforms and news feeds. What begins as a brief, condensed moment of intensified politicism spreads from screen to screen like a political contagion, producing divergent effects depending on the viewer’s pre-existing mazeway of cognition.

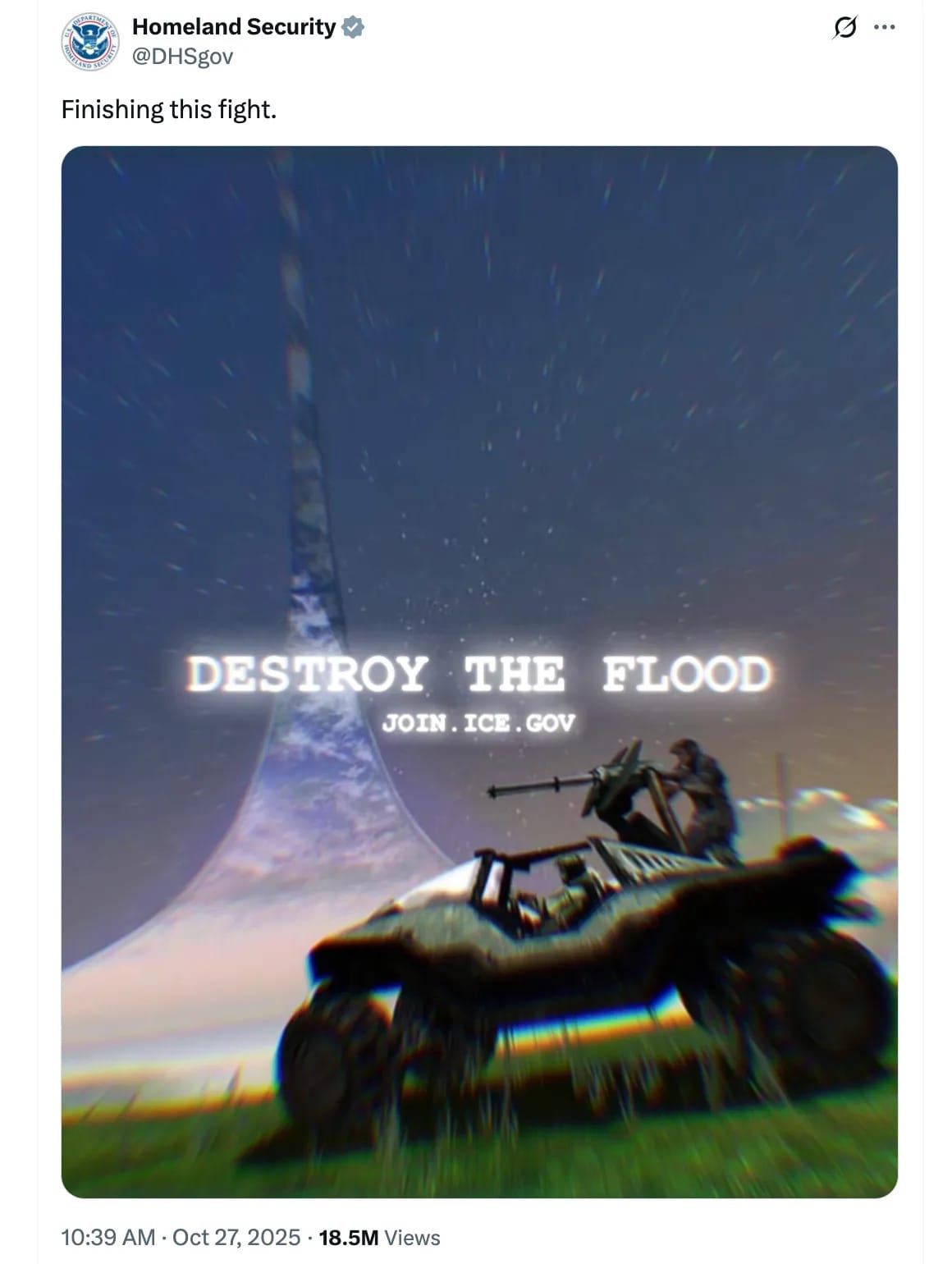

ICE is fully ready and primed for carrying out ideological violence, and this is not rhetorical excess. Under the Trump administration, ICE recruitment practices and institutional signaling were deliberately oriented toward young men and adjacent demographics—such as gamers—perceived as especially predisposed to extra-legal or quasi-legal violence when shielded by the legitimacy of a policing apparatus. The result has been the mobilization of nativist and nativist-adjacent fantasies into a pre-existing state institution. Importantly, Trump did not create ICE; it already existed within the liberal state’s infrastructural capacity for immigration enforcement. Its prior institutional embeddedness made it especially amenable to rapid weaponization for intensified and excessive nativist action. ICE itself is a modern relic of the Bush administration’s War on Terror, carrying forward logics of internalized exception and permanent security threat.

ICE’s deployment as an ethnocratic instrument is often compared to Nazi Germany’s Gestapo. However, if a parallel example must be drawn from outside the United States, Being prefers to point instead to Apartheid South Africa. There, the enforcement of “apartness” depended on constant police incursions into civic space, repeatedly reminding the population that democracy and rights were reserved only for those classified as white and compliant with racial separation from those classified as Black. The power of the regime lay not merely in law, but in the everyday theatricality of its enforcement.

Ultimately, however, it is not even necessary to look beyond the United States for such examples. The U.S. itself once contained a regional ethnocracy in the South, one that relied on local police departments and municipal and state governments to routinely enforce racial violence and segregation. Popular liberal news anchors and talking heads are quick to shout “Nazi! Nazi! Nazi!”—yet this reaction conveniently forgets that the United States, like many other liberal states, was founded atop the dispossession, bloodshed, and enslavement of Indigenous peoples and ethnic minorities.

Running parallel to Trump’s administrative strategy of blunt brutality has been an effort to secure judicial validation. By pressuring the Supreme Court and lower federal courts to endorse expanded executive latitude in immigration enforcement, Trump sought to formalize a bifurcated legal order—one of the necessary preconditions for the emergence of ethnocratic governance. Yet the judiciary has not offered unqualified endorsement. Instead, hesitation and fragmentation within the courts have obstructed consolidation, forcing the administration to rely increasingly on informal, discretionary, and procedurally unstable mechanisms of enforcement.

Another obstacle to the realization of a coherent ethnocratic project has been Trump himself. His political pathology—marked by vanity, impulsivity, and an inability to discipline messaging—has repeatedly undermined strategic coherence within his own movement. These traits produce rhetorical and tactical excesses that erode his capacity to sustain a stable ideological horizon for his base. The episode surrounding the capture of Maduro illustrates this dynamic: rather than consolidating “America First” nationalism, the event reframed the slogan into something closer to “America’s backyard first,” alienating segments of the MAGA coalition already skeptical of imperial overreach.

The capture of Maduro thus functions as a parody of the Iraq War, which was itself a parody of the Cold War. In a similar recursive fashion, contemporary attempts to re-institute ethnocratic rule operate as a parody of Southern segregationism, which was itself a degraded echo of the slave system. This recursion invites reconsideration of Marx’s famous formulation that history repeats itself “first as tragedy, then as farce.” What follows the farce may be neither renewed tragedy nor simple repetition, but a phase best described as pure cynicism.

This cynicism is especially visible in the contemporary media environment. The rapid circulation of memes—such as those grotesquely satirizing Renee Good’s death—demonstrates how political violence is increasingly metabolized as ironic spectacle. This mirrors earlier memetic treatments of George Floyd by segments of the political right, as well as by those who posture as “politically neutral” through ironic detachment. The internet, in this sense, is not unreal; it is an unreality constructed from the raw materials of the real, a space in which violence is neither denied nor confronted but endlessly distorted into consumable absurdity.

Perversely, these ongoing displays of terror do not simply signal authoritarianization. Rather, they point toward what can be described as a democratization of difference, in which a supposedly homogeneous native people—often excluding the actually indigenous—are encouraged to directly enact their will to reinforce divisions between themselves and those they frame as elites or agents of foreign override of national sovereignty. To rule as an authoritarian is to impose top-down depoliticization and widespread civic passivity; to rule as an antagonitarian regime is instead to institutionalize power along a horizontal axis. This axis mobilizes segments of the population into an active and incentivized us-versus-them dynamic, transforming civilians into political agents acting against designated enemies in civic space. In Trump’s case, this means feeding off America’s cultural reverence for democracy and freedom to produce a form of constitutionalized violence against specific populations.

If anarchists are to meaningfully confront the re-emergence of ethnocracy, one of its core mechanisms must be clearly understood: what we will call legal apartness. Legal apartness is a form of legal dualism in which legality itself is separated along ethnic lines. No ethnocratic project can succeed without the strong arm of a court system capable of producing two legal realities. One set of juries, judges, lawyers, and trials exists for the “pure ethnos,” and another for those outside it. To realize this legal bifurcation—which first exists in the minds of ethnocratic forces—is to transform the interior national territory into two distinct territories: the ethnonational territory and the contested multi-ethnic territory. Because this is a re-emerging ethnocracy, rather than an initial settler-colonial project in which the entirety of the land can be declared “contested” and ethnonational territory can then be clearly demarcated from the outset, these two territories now overlap extensively. This overlap is the historical result of the enfranchisement of minority rights and their associated institutions. Consequently, the active invasion of civic space requires the systematic breakdown of this overlap and its institutions in order to re-manufacture division and progressively erode the shared terrain.

Because sovereign power in nation-states is centrifugal—emerging from the territorial periphery—any struggle over state power must also think centrifugally. This does not imply clearly drawn fronts or stable territorial lines, as in older civil wars. Instead, contemporary conflict is defined by asymmetry, mobility, and sporadic maneuvering. Within this framework, the Trump administration has effectively designated Minnesota—a border state with Canada and thus centrifugally valuable—as a contested multi-ethnic territory, with Somali residents in particular being politicized as the primary “threat” to national coherence. Renee Good, as a consequence of this designation, becomes an early victim of this spatial logic. Her whiteness is rendered invalid, reframed as having been “lost” to radical left polarization. She is positioned as someone who might have belonged to the ethnonational project but instead became an internal enemy. In this way, the administration carves up the United States not through formal partition, but by weaponizing the spaces in between.

As Oren Yiftachel directly said, “Such a regime’s main goal is to maximize ethnic control over a contested multi-ethnic territory and its governing apparatus.”

Tim Walz may not recognize it, but his state government is engaged in an unofficial war with the federal government—silent in that no formal lines have been drawn, yet loud in that open violence is already occurring. The most unsettling prospect of a second American civil war is not the spectacle of opposing uniforms exchanging fire, but the possibility that no one will know it is happening at all until historians later declare that it had been underway for years. Past ethnocracies offered clarity through signage, laws, and explicit territorial demarcations. Knowing which water fountains were for whom or which territories were Bantustans has become anachronistic. The ethnocracies of the unfolding future will provide no such transparency. The world itself increasingly resembles a single contested multi-ethnic territory, and there will be no luxury of posted signs to tell us where we stand.

Any struggle against an ethnocratic regime necessarily entails the re-contestation of the whole spatial dimension itself. This means resisting ethnonational dominance wherever it seeks to territorialize social life and organizing as a consciously multiethnic force capable of undermining attempts to create, stabilize, and expand ethnonational territory. The re-formation of the ethnonation must be actively blocked, not merely opposed rhetorically, insofar as its power depends on the continual production of bounded identity, homogenous territory, and exclusionary belonging. In this sense, any effective counter-project requires a multicultural insurrection: a refusal of ethnonational coherence through collective heterogeneity.

Liberals and vertically oriented socialists may pursue this objective through state reorganization, legal restructuring, or the strategic deployment of multicultural space within existing institutional frameworks. For them, the goal is often the construction of a plurination—an ordered plurality managed through formal governance, rights regimes, and territorial inclusion. While this approach may succeed in limiting the most explicit forms of ethnocratic rule, it remains committed to the preservation of nationhood and spatial sovereignty as such.

This path, however, is not available to anarchists. Anarchism seeks neither nations nor plurinational states, but the abolition of the nation-form altogether. Its horizon is one in which all spaces are freed from compulsory identity and allowed to blossom into a dense mesh of voluntary, horizontal, and overlapping associations. Consequently, when anarchists weaponize multicultural territory, they do so not to stabilize diversity within borders, but to dissolve the very spatial logics that make supremacy and assimilation possible.

The aim, then, is the creation of a xeno-cultural non-spatiality: a mode of social existence resistant both to domination and to incorporation, in which difference proliferates without being territorialized, ranked, or absorbed. To “wage war against space” in this sense is not to pursue conquest, but to negate the spatial abstractions—border, homeland, inside/outside—upon which ethnocratic power depends. What emerges in their place is not a unified people, but multitudes: blurred collectivities of peoples, strangers, hybrids, aliens, and monsters, bound not by blood or soil, but by the shared culture of anarchism and the refusal of all supremacist and governmental orders.

Sources and further reading:

- Benedict Anderson - Imagined Communities: Reflections on the Origin and Spread of Nationalism

- Roger Griffin - Interregnum or endgame? The radical right in the ‘post-fascist’ era

- Cas Mudde and Cristóbal Rovira Kaltwasser - Populism: A Very Short Introduction

- Post-Comprehension - Life, Liberty, and the pursuit of Likeness (https://medium.com/@postcomprehension/life-liberty-and-the-pursuit-of-likeness-6a2b1b9ebcda)

- Oren Yiftachel - Ethnocracy: Land and Identity Politics in Israel/Palestine