May Day, The Haymarket Martyrs, and Indigenous Resistance | Jeff Shantz (Canada, 2025)

The connections between the Chicago anarchists and the Metis rebellion may seem like historical footnotes. Indeed, they have been largely overlooked. However, they should be viewed as integral parts of anarchist praxis at the time and reveal more deep understandings of the importance of Indigenous land defense within active working-class anarchist circles than is sometimes assumed.

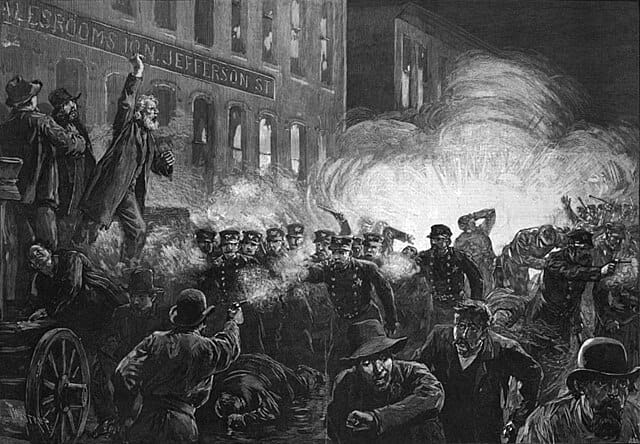

It is widely understood amongst anarchists that May Day has its origins in state repression and police violence against class struggle anarchists in Chicago fighting for the eight-hour day—and memorializes the anarchist Haymarket Martyrs killed by the state. What is less widely known is that the Haymarket anarchists were staunch supporters of Indigenous struggles against capitalist colonization—including for the reclamation of land by Indigenous peoples—what today would be called land back.

This solidarity included writing articles in support of Indigenous struggles in their newspaper, The Alarm. More than that it included direct relationships with, and mutual aid, for those involved in the 1885 North-West Rebellion of Métis, Cree, and Assiniboine against Canadian colonialism in what is today called Saskatchewan and Alberta (then Nort-West Territories).

An article of April 18, 1885, in the Chicago anarchist journal, The Alarm, squarely placed the North-West Rebellion in the context of capitalist enclosure and land theft. This is the basis of the uprising. It shows an early expression of anarchist solidarity with Indigenous land struggles and fights for what today would be called land back. It unambiguously calls for the deaths of the enclosers.

“The rebellion in the northwest headed by Riel has its inception in the effort of Canadian land-sharks to deprive these people of the Saskatchewan valley of their homes, since they braved the rigors of the climate and the privations of frontier life to settle these lands and open them to cultivation. They are fighting the land pirates who seek to deprive them of their years of hard toil. They are struggling to retain their homes of which the statute laws and chicanery of modern capitalism seeks to dispossess them. May their trusted rifles and steady aim make the robbers bite the dust.”1

On October 31, 1885, The Alarm published a tribute to Riel following his execution. It compared him to John Brown. After documenting various efforts of the Métis and allied First Nations to resist enclosure and occupation by government agents, corporations, and settlers, the article asserts,

“Finally their patience was broken. They arose; they revolted. At the head of the rebellion appeared Louis Riel, the son of those northern deserts, where every man having a carabine on his shoulder or a knife in his girth is an equal of all under the large, impartial heaven. With his little troops of hardened, intrepid partisans Riel conducted the campaign for months…

One against hundred, the half-breed, insurgents, strengthened by the justice of their cause, fought like lions. Many a hero fell on the field of battle. Riel multiplied himself, inflaming his combatants, always first in the fire, always indefatigable. But one day, overpowered by the numbers of the enemy and having fought until his strength deserted him, he was vanquished…

They declared him guilty, guilty of having fought to be free himself and to free his people, and condemned him to death.”2

A November 28, 1885, reports that “The American Group of the International held a well attended mass meeting at 54 West Lake street Sunday afternoon to pay homage to the martyred heroes to human liberty,” which included Louis Riel. After a speech by Albert Parsons, the meeting passed the following resolution:

“Resolved, By this meeting of Anarchists that we express our solidarity with Comrade Julius A. Lieske, who was murdered last Tuesday in Kossel; and Louis Riel, who was strangled last Monday at Regina. Progress and liberty move upon the corpses of heroes, slain by “social order.” Down with the strumpet!”3

The connections between Chicago anarchists and the Métis rebellions also had some interesting interpersonal connections. Among these was the involvement of Riel’s secretary, Honoré Jaxon, in the Chicago labor movement after his escape and flight following arrest and detention after Riel’s execution.

Honoré Jaxon, aka William Henry Jackson, was Riel’s secretary leading up to the North-West Rebellion. Intelligence reports of the North West Mounted Police (NWMP), precursor to the modern Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), concluded that “Jaxon seems to be a right hand man of Riel … I believe he does more harm than any Breed among them.”4 With suppression of the uprising, Jaxon was arrested and charged with felonious treason. He was spared execution only when the courts declared him insane and had him committed to a mental institution near Winnipeg.

Quickly after arrival in Chicago Jaxon threw himself heavily into the campaign for the eight-hour workday and, after Haymarket, the defense of the anarchist Haymarket Martyrs. He would also help organize the World Conference of Anarchists there. In a 1911 article in Mother Earth, Jaxon recalled that a comrade “sped me on my way with a sincere introduction to Albert R. Parsons and other comrades, who were shortly to seal their devotion with their lives…I found myself within three months placed in charge of the successful eight-hour fight of the Chicago carpenters.”5

The connections between the Chicago anarchists and the Metis rebellion may seem like historical footnotes. Indeed, they have been largely overlooked. However, they should be viewed as integral parts of anarchist praxis at the time and reveal more deep understandings of the importance of Indigenous land defense within active working-class anarchist circles than is sometimes assumed.

These relationships, and anarchist solidarity with Indigenous struggles, have much to suggest to us in a contemporary context, particularly in terms of anarchist engagement with anti-colonialism, Indigenous sovereignty and land back struggles, and national liberation within a context of working-class internationalism.

First published on Liberté Ouvrière on July 24th 2025

Notes

1. The Alarm. 1885. “The Riel Rebellion.” April 18. https://mgouldhawke.wordpress.com/2022/12/26/a-martyr-the-alarm-1885/

2. The Alarm. 1885. “A Martyr.” October 31. https://mgouldhawke.wordpress.com/2022/12/26/a-martyr-the-alarm-1885/

3. The Alarm. 1885. “Two Martyrs: Memorial Services Held by Working People Over the Murder of Lieske and Riel.” November 28. https://mgouldhawke.wordpress.com/2022/12/26/a-martyr-the-alarm-1885/

4. Christy, Jim. “Scalawags: Honoré Jaxon.” NUVO. https://nuvomagazine.com/magazine/summer-2012/scalawags-honore-jaxon?srsltid=AfmBOorMJ5ddo0LkzYWM_CSfUHNfLVMpI24Xh7ZotdLu65556RkYNNjo

5. Jaxon, Honore J. 1911. “A Reminiscence of Charlie James.” Mother Earth. https://mgouldhawke.wordpress.com/2023/10/02/a-reminiscence-of-charlie-james-honore-j-jaxon-1911/

References

Christy, Jim. “Scalawags: Honoré Jaxon.” NUVO. https://nuvomagazine.com/magazine/summer-2012/scalawags-honore-jaxon?srsltid=AfmBOorMJ5ddo0LkzYWM_CSfUHNfLVMpI24Xh7ZotdLu65556RkYNNjo

Jaxon, Honore J. 1911. “A Reminiscence of Charlie James.” Mother Earth. https://mgouldhawke.wordpress.com/2023/10/02/a-reminiscence-of-charlie-james-honore-j-jaxon-1911/

The Alarm. 1885. “The Riel Rebellion.” April 18. https://mgouldhawke.wordpress.com/2022/12/26/a-martyr-the-alarm-1885/

The Alarm. 1885. “A Martyr.” October 31. https://mgouldhawke.wordpress.com/2022/12/26/a-martyr-the-alarm-1885/

The Alarm. 1885. “Two Martyrs: Memorial Services Held by Working People Over the Murder of Lieske and Riel.” November 28. https://mgouldhawke.wordpress.com/2022/12/26/a-martyr-the-alarm-1885/